Being a lover of textiles, especially those from Japan, I made sure I didn't miss the 'Boro - The Thread of Life' exhibition recently held at Kimono House in Melbourne.

Boro can be translated as 'rags' but the term is also used to describe pieces of clothing or household items that have been patched and repaired many times. The practice originated out of necessity - people in rural areas were poor and were not able to go out and buy new clothing or bedding, so existing items had to be patched and re-patched. Patching was done with whatever fabric the sewer had on hand - there was no conscious design and planning process - it was utilitarian patching. Fabric was precious - many pieces were originally hand loomed and hand woven and dyed with indigo or other botanic dyes. Carefully saved fabric swatches and boro would be passed on to the following generations to use.The repeated repairs made over generations resulted in unique pieces that often showcased various stitching techniques such as sashiko. These boro became pieces of family history and had great sentimental value.

The practice pretty much died out when mass-scale production became commonplace and as a result interest in these pieces dwindled. These days, however, they are recognised as a part of Japan's cultural history and are highly collectible.

Some of the pieces that were on display are shown below. I apologise for the poor quality photos - they were taken on my phone which is now at the very trailing end of technology.

A farmer's vest:

A child's kimono:

Some futon covers:

This following piece was pretty special. It is a farmwoman's jacket that had been carefully patched, sashiko stitched and then overdyed in natural indigo. The collar was replaced and and the patching of the body of the garment has been so carefully done that, when combined with the rows of sashiko stitching and the overdyeing, render the repairs almost invisible. It was so beautifully made.

It's interesting that everyday items, patched out of necessity to enable continued use, are now considered pieces of art. I think it's a reflection on our throw-away society and how little value most people place on things they own. Many of the pieces on display were over 100 years old and have seen many years of use. How common would that be today?

From a permaculture perspective I also appreciate the practicality and recycling nature of Boro - why discard something if it can be mended? And when it gets past being able to be mended for use in it's original purpose, it can still be of use as a patching material, or even a rag.

And finally from a textile lover's perspective I loved seeing the beautiful indigo pieces that were used as patching. The sewer used whatever fabric they had on hand but the end result is a harmonious piece that has it's own unique beauty.

Sunday, 21 February 2016

Saturday, 20 February 2016

Basket making demonstration

In early February, we attended a basket making demonstration by Sue Dilley, president of Basketmakers Of Victoria. It was one of the many interesting events organised by our local permaculture group.

Sue took us through a wonderful display of different baskets made from native and exotic plant fibres.

She explained how to select and dry the plant material and gave us plenty of tips:

Spinifex - Here's a basket Sue made from spinifex grass using a darning needle and cotton thread:

Watsonia - a weed in many areas, this can be collected when it dries on the plant. It has a lovely chestnut colour.

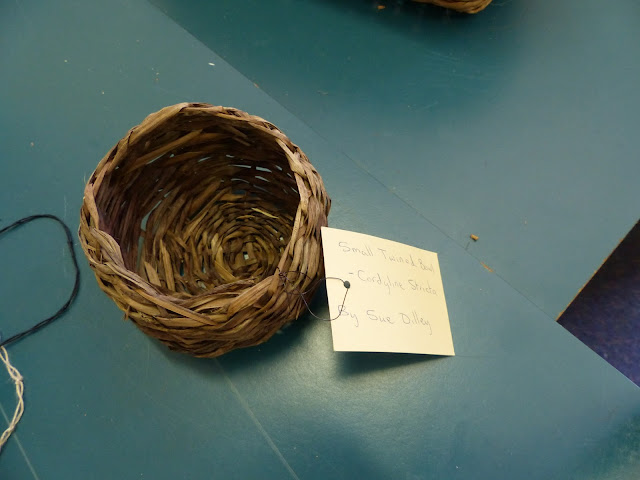

Cordyline - Cordyline australis is a tough fibre and can be collected as it drops off the plant. However if you pull it off when fresh the leaves will be in better shape (no stringy bits to them). Cordyline stricta is a lighter fibre than australis, but still good for basketmaking. Here's a basket Sue made from stricta:

Red Hot Poker(Kniphofia)- these should be collected green, after the plant has flowered

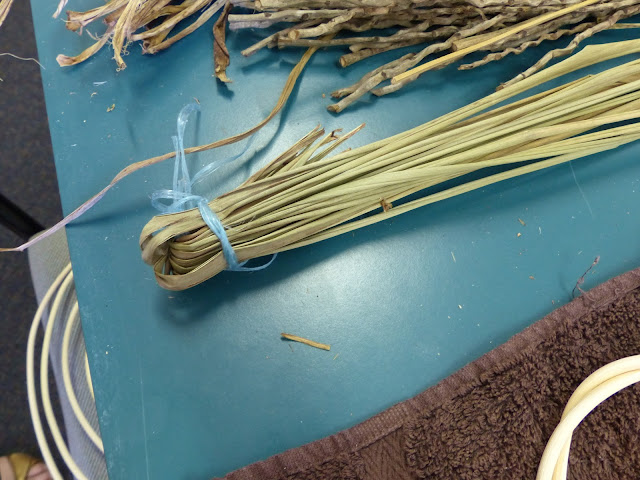

Bullrush - collect in January by cutting as low in the water as you can. Strip off the leaves and collect at the tip of the stalk, fold it over, tie and hang up to dry. You can see an example of how to tie the stalks in the picture below

Passionfruit vine - this can be used fresh or it can be coiled up until ready to use when it will need to be rehydrated slightly. Rehydration may take a couple of days if the vine is thick.

Here's a picture of a basket Sue made from passionfruit vine:

Fruit tree prunings are also a great basketmaking fibre. Sue had several examples of baskets she'd made from fruit tree prunings.

The basket below was made from apple prunings:

And this basket was made from olive prunings:

As an unexpected bonus, we all got to have a go at basket-making in the form of a small tension tray. As the name suggests, it is the tension between the branches that holds the tray together. Here's a tension tray Sue made from black willow:

Sue had kindly already cut and pre-soaked the cane for us to use. A quick demonstration and we jumped in and had a go.

Here's mine in progress:

And the finished product:

The whole experience was a lot of fun and we were very fortunate to have an expert such as Sue who was kind enough to give up her time to spend with us.

To finish this post I have to show you my favourite of all the baskets, one made from fallen Jacaranda leaf stalks. Isn't it gorgeous?

If you are interested in basketmaking, you should definitely check out the Basketmakers of Victoria website. They run a lot of events and classes where you can learn to make your own beautiful baskets.

Sue took us through a wonderful display of different baskets made from native and exotic plant fibres.

She explained how to select and dry the plant material and gave us plenty of tips:

- Drying should be done in the shade

- If you don't plan to use your dried plant material immediately, then it should be stored wrapped up in butcher's paper to keep it clean and dry, and with the paper labelled to identify contents.

- Vines - to be suitable for basketmaking they must be able to wrap around your finger 3 times without breaking

- Leaves should be generally be collected after the plant has flowered and then dried.

- Grasses - to dry these, spread them on newspaper and each day move the grass around so it dries completely

Spinifex - Here's a basket Sue made from spinifex grass using a darning needle and cotton thread:

Watsonia - a weed in many areas, this can be collected when it dries on the plant. It has a lovely chestnut colour.

Cordyline - Cordyline australis is a tough fibre and can be collected as it drops off the plant. However if you pull it off when fresh the leaves will be in better shape (no stringy bits to them). Cordyline stricta is a lighter fibre than australis, but still good for basketmaking. Here's a basket Sue made from stricta:

Red Hot Poker(Kniphofia)- these should be collected green, after the plant has flowered

Bullrush - collect in January by cutting as low in the water as you can. Strip off the leaves and collect at the tip of the stalk, fold it over, tie and hang up to dry. You can see an example of how to tie the stalks in the picture below

Passionfruit vine - this can be used fresh or it can be coiled up until ready to use when it will need to be rehydrated slightly. Rehydration may take a couple of days if the vine is thick.

Here's a picture of a basket Sue made from passionfruit vine:

Fruit tree prunings are also a great basketmaking fibre. Sue had several examples of baskets she'd made from fruit tree prunings.

The basket below was made from apple prunings:

And this basket was made from olive prunings:

As an unexpected bonus, we all got to have a go at basket-making in the form of a small tension tray. As the name suggests, it is the tension between the branches that holds the tray together. Here's a tension tray Sue made from black willow:

Sue had kindly already cut and pre-soaked the cane for us to use. A quick demonstration and we jumped in and had a go.

Here's mine in progress:

And the finished product:

The whole experience was a lot of fun and we were very fortunate to have an expert such as Sue who was kind enough to give up her time to spend with us.

To finish this post I have to show you my favourite of all the baskets, one made from fallen Jacaranda leaf stalks. Isn't it gorgeous?

If you are interested in basketmaking, you should definitely check out the Basketmakers of Victoria website. They run a lot of events and classes where you can learn to make your own beautiful baskets.

Monday, 15 February 2016

Summer honey harvest

At the end of January we harvested 6 full-sized frames of honey from our backyard hive. Not as much as last year, but hey, once we make sure we leave enough honey for the bees, we're happy with whatever excess we get.

Here's the result:

And here's the crushed, sticky comb that's left over after all the honey has drained through:

We'll turn that into clean wax. As you can see the comb was pretty dark and it didn't crush all that easily ...so we may have to try this technique to separate out the wax, rather than the more simple oven method described here. The final step will be to purify the wax using the solar method, as described here.

Here's the result:

We'll turn that into clean wax. As you can see the comb was pretty dark and it didn't crush all that easily ...so we may have to try this technique to separate out the wax, rather than the more simple oven method described here. The final step will be to purify the wax using the solar method, as described here.

Sunday, 14 February 2016

Preserving Olives - a success

A while back we posted how we tried the technique of preserving olives in brine. Previously we've preserved fruit using a Fowlers Vacola - which cooks the contents of the jars - and also dehydrated fruit and tomatoes using various methods. Preserving olives was our first go at preserving using brine. We followed the recipe outlined in Preserving the Italian Way by Pietro Demaio with some slight modifications such as slitting the olives to speed up the process and not adding any herbs or spices to the brine. The recipe stated that the olives could be eaten after 6 months. As we slitted ours, they would have been ready earlier, but we still left them for about 6 months.

This week we opened one of the jars to have a taste. There was some gas buildup which could be due to the olives fermenting a bit or possibly indicating that the preservation technique hadn't worked properly and that the olives might be contaminated. There is a risk of dangerous contamination and food poisoning with any preservation technique. A quick check on the internet had several sources saying that some gassing with this technique was OK although one source said that the gas indicated we should throw them out. Feeling a bit more confident we went ahead and had a taste. We drained the brine off (by this point in the process it is very bitter) and rinsed the olives under running water before tasting a couple. They tasted great! Being cautious by nature, we waited a week - no trip to the hospital with botulism or other food poisoning observed - before deciding that the process had been a success for that jar at least :)

For the remaining jars, we made up a new brine solution. Our recipe recommended a 6% brine (i.e. 60 grams salt per litre of water). As was the case in the original recipe, the brine was poured hot into the jars and then they were sealed. According to the recipe we followed, these olives should store for a year.

The olives we tasted from the original jar were put into a fresh jar with olive oil. Yum!

We found that preserving olives in brine is a quick, inexpensive preservation method that keeps the shape and colour of the olives. A method we'll definitely be using again.

This week we opened one of the jars to have a taste. There was some gas buildup which could be due to the olives fermenting a bit or possibly indicating that the preservation technique hadn't worked properly and that the olives might be contaminated. There is a risk of dangerous contamination and food poisoning with any preservation technique. A quick check on the internet had several sources saying that some gassing with this technique was OK although one source said that the gas indicated we should throw them out. Feeling a bit more confident we went ahead and had a taste. We drained the brine off (by this point in the process it is very bitter) and rinsed the olives under running water before tasting a couple. They tasted great! Being cautious by nature, we waited a week - no trip to the hospital with botulism or other food poisoning observed - before deciding that the process had been a success for that jar at least :)

For the remaining jars, we made up a new brine solution. Our recipe recommended a 6% brine (i.e. 60 grams salt per litre of water). As was the case in the original recipe, the brine was poured hot into the jars and then they were sealed. According to the recipe we followed, these olives should store for a year.

The olives we tasted from the original jar were put into a fresh jar with olive oil. Yum!

We found that preserving olives in brine is a quick, inexpensive preservation method that keeps the shape and colour of the olives. A method we'll definitely be using again.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)